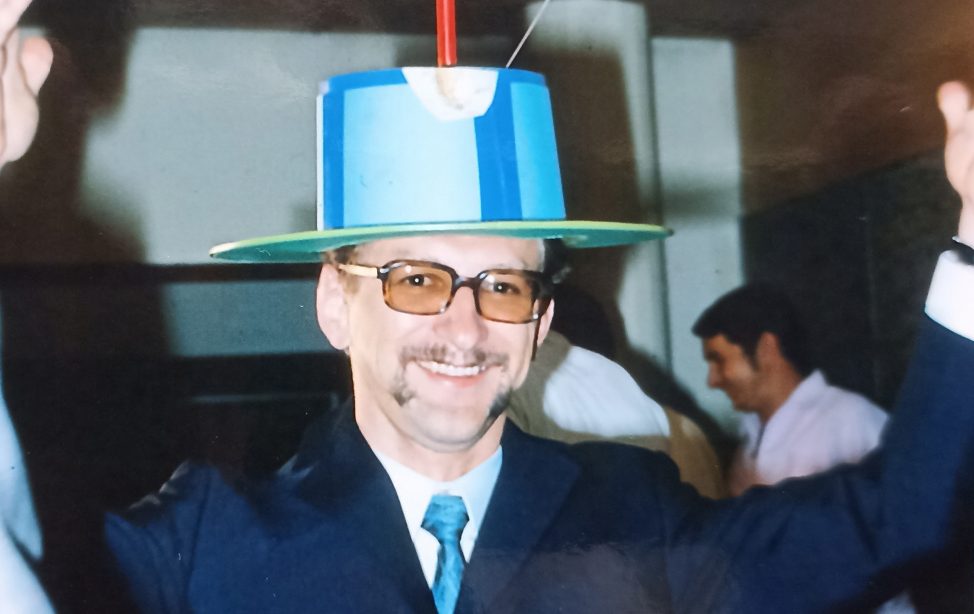

TUM alumnus and Nobel Prize winner Joachim Frank (Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM).

In this interview, he talks about his childhood in bombed-out Siegen, why he stuck with his research idea despite the obstacles he faced and the magical moments he experienced during the Nobel Prize award ceremony.

Picture: Magdalena Jooß/ TUM

Picture: Magdalena Joos/TUM

Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM

Wenn ich mich nur auf die Wissenschaft beschränken würde, dann würde ich von großen Teilen der Welt nichts mitbekommen.

The Nobel Prizes are traditionally conferred in the Konserthuset, the concert hall in Stockholm, in the presence of the royal family. King Gustav himself presents the popular medal and the certificate (Photo: Alexander Mahmoud/ Nobel Media AB).

On December 10 the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was conferred to TUM Alumni Joachim Frank in Stockholm (Photo: Alexander Mahmoud/ Nobel Media AB).

TUM alumnus and Nobel Prize winner Joachim Frank (Picture: Magdalena Jooß/TUM).

Doctorate Physics 1970

Joachim Frank was born in Weidenau, which today is a district of Siegen. After his intermediate examination in Freiburg, he graduated as a physicist from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. In 1970, Joachim Frank received his doctorate from the pioneer of Electron Microscopy, Prof. Walter Hoppe at TUM with a thesis on high-resolution electron micrographs using image difference and reconstruction methods.

As a postdoctoral fellow he worked at the California Institute of Technology, at the University of California, at Berkeley and Cornell University. From 1972, Frank was a research assistant at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, and from 1973 he was the Senior Research Assistant at the University of Cambridge. Since 1975 Frank has been working at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health (University at Albany, The State University of New York).

Since 1997 Frank has also held a Research Professorship in Cell Biology at the New York University and since 2008 he has held a Professorship in Biochemistry, Molecular Biophysics and Biological Sciences at Columbia University. Joachim Frank has made significant contributions to cryo-electron microscopy of single molecules and was able to contribute substantially to understanding the structure and function of ribosomes using the resulting electron-microscopic images. In 2017 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with Jacques Dubochet and Richard Henderson. Joachim Frank is married and has two children.