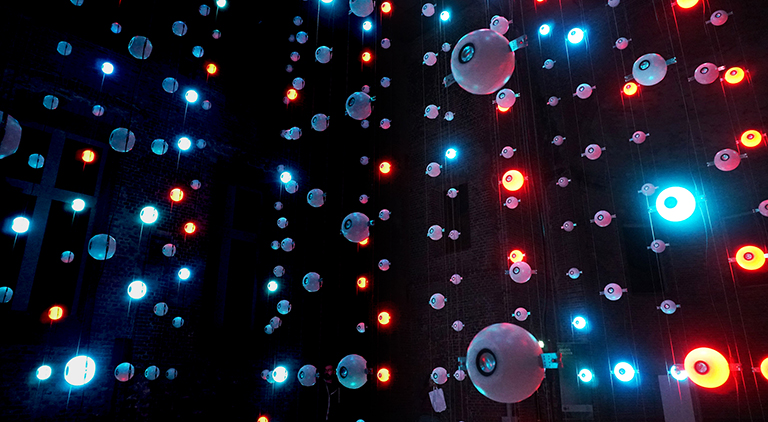

For almost twenty years, TUM Professor Dr. Elisa Resconi has been hot on the heels of neutrinos. To capture these extremely volatile elementary particles from distant galaxies, she had glass spheres placed deep under the ice of the South Pole in her IceCube Experiment (photo: Magdalena Jooß / TUM).

Her participation in the experiment set the course for Elisa Resconi’s future in two ways: it sparked a boundless passion for the study of neutrinos. And she met her husband, the Experimental Physicist and TUM Professor Dr. Stefan Schönert.

On October 26, 2021, Elisa Resconi will speak at Women of TUM Talks on the topic of "Power, Strength and Energy" and provide interesting insights into exploring the most energetic and extreme aspects of our universe. Image: Magdalena Jooß/TUM.

Neutrinos are the most common elementary particles in the universe. Some originate from the center of the sun as a result of its continuous nuclear fusion. Others are of cosmic origin from billions of light years away. They can be used to observe phenomena in cosmic accelerators and collapsing stars that would otherwise remain hidden. “They are a window into the universe,” Elisa Resconi says. “I’m always most interested in what is least known and most challenging.”

Neutrinos are very difficult to observe. In complete darkness, specialized telescopes have to be pointed at large areas in order to detect the volatile particles and the minimal flashes of light they emit. That’s why neutrino telescopes are located at extreme places – deep underground, thousands of meters under Antarctic ice, or at the bottom of Lake Baikal in Siberia.

At TUM, I can conduct my research in a way that is possible only in a few other places in the world.

Holding the Chair of Experimental Physics with Cosmic Particles at TUM, Elisa Resconi has been in charge of these unusual telescopes since 2012. She could not have wished for a more suitable research location. “With the high density of experts in Astrophysics and Particle Physics at TUM, I have constant access to the latest discoveries,” she says. “Here, I can conduct my research in a way that is possible only in a few other places in the world.”

For years, Elisa Resconi and her research group have been analyzing the data that neutrino detector IceCube sends them from the South Pole. Based on this data, she was one of the first scientists worldwide to identify blazars as a source of cosmic neutrinos in 2017. That same year, she launched the Pacific Ocean Neutrino Experiment, which serves as a preliminary study for the construction of a multi-cubic-kilometer neutrino telescope in the Pacific Ocean.

For this study, Elisa Resoni had glass spheres anchored to steel cables at a depth of 2600 meters off the Pacific coast of Canada. The spheres contain optical sensors that are to pick up the neutrino signals even better than the Antarctic IceCube. Four of the spheres also contain small works of art. Artist Jol Thomson, for example, is using the Internet to send texts and sounds into his sphere. Artist Lea Vajdas hopes that her sphere will glisten in rainbow colors when fluorescent deep-sea inhabitants take up residence on it.

The combination with art has a long tradition in Elisa Resconi’s research. The sound artist Tim Otto Roth, for example, translated the data collected by the Antarctic neutrino telescope into sounds and colors in his installation AIS³ (Ais-Cube). In another interdisciplinary project, TUM artists and physicists went on an excursion to the underground laboratory in the Gran Sasso mountain massif and subsequently worked on joint epistemic objects dedicated to dark matter and neutrinos.

In these art projects, it is very important to Elisa Resconi that the scientific basis is always accurate and transparent. These transdisciplinary art projects not only enable researchers to reflect on their own work. Especially laypersons, who normally do not deal with Particle Astrophysics, can be reached through the artworks. “Even if all that sticks is the word neutrino, we have gained something,” Elisa Resconi says. “Science and the Arts is what defines our culture – not money, not ego.”

On the 26th of October 2021, Elisa Resconi will be speaking on the topic of “Power, Strength and Energy” at the Women of TUM Talks, providing interesting insights into exploring the highest-energy and most extreme aspects of our universe.

444 illuminated loudspeakers transform TUM Professor Elisa Resconi's research into a walk-in piece of art (photo: Tim Otto Roth / imachination projects).

Elisa Resconi (Image: Private).

TUM-Professorship Experimental Physics with Cosmic Particles

In 1995, Elisa Resconi, born in Brescia, Italy, completed her Master’s degree in Physics at the Universitá degli Studi di Milano. She followed this with a Doctorate at the Universitá degli Studi di Genova and the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso in Italy in 2001. With the Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow grant, Elisa Resconi conducted research at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY of the Helmholtz Association in Zeuthen/Berlin, and as an Emmy Noether junior research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg. After a position as visiting professor at Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, she came to TUM in 2012, where she held a Heisenberg professorship from 2013 to 2016. In 2018, she was awarded the TUM Liesel Beckmann Distinguished Professorship.

The passionate Astrophysicist lives and works in Munich with her husband, TUM Professor and Alumni Dr. Stefan Schönert (Diploma Physics 1990, Doctorate 1995), and their two children. Their living room frequently becomes an arena for heated discussions about dark matter, black holes, and cosmic rays. Only her children Emma and Emil are able to limit the evening discussions and see to a healthy equilibrium in the family.